There it is, gleaming at the top of your LinkedIn feed: your dream job, a high-level, well-paying position in your field. Are you qualified enough? Should you apply? New research shows that women might be less likely to take that chance than men.

Talented women are more likely to shy away from applying for job opportunities, particularly more advanced, higher-paying positions, because they’re concerned they aren’t qualified enough, whereas men don’t seem to worry about their skills matching the specific job requirements as much, according to research by Harvard Business School Associate Professor Katherine B. Coffman that was recently published in the journal Management Science.

Women tend to avoid applying for advanced positions where men are stereotypically believed to have an advantage, such as more analytical or management-oriented roles, according to the research, coauthored with Manuela R. Collis and Leena Kulkarni, former research associates at Harvard Business School.

“We found that candidates were talented, and yet they self-selected out,” Coffman says.

Ultimately, that means many businesses advertising for executive positions may wind up with applicant pools that are dominated by men, simply because women are more hesitant to dive in, a scenario that likely contributes to a gender gap in wages and positions that has persisted for decades. In 2023, the World Economic Forum declared that despite slow and steady gains in the proportion of women hired to leadership positions in the past eight years, at the current rate of change, the global gender gap is still 130 years away from closing.

Coffman’s research study was inspired by a commonly quoted statistic: Men apply for a job when they meet only 60 percent of the qualifications, but women apply only if they meet 100 percent of them.

“You hear this so much because it resonates with people, so we set out to do empirical work around that: Is this indeed the pattern we see in an experimental context? If it is, what might we be able to do about it?” she says.

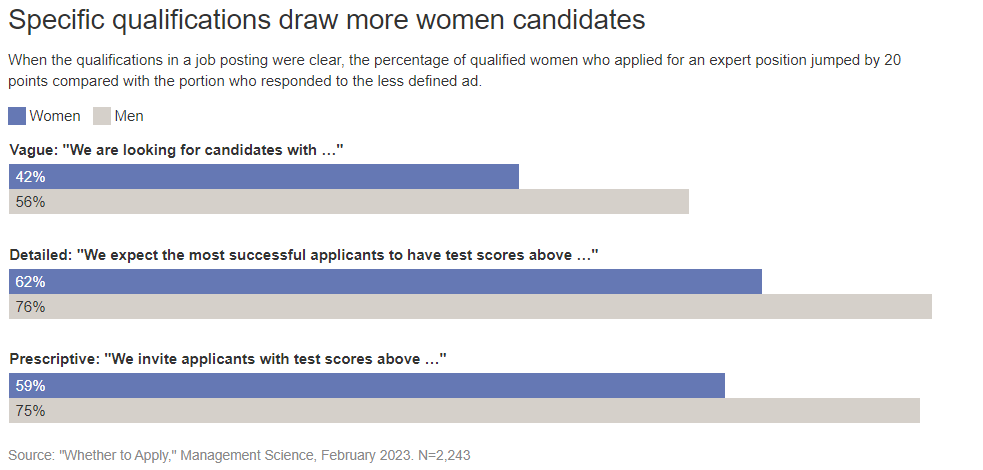

As it turns out, Coffman’s research reveals that organisations can take a simple step to draw more women to apply: Make it easier for candidates to know whether they are qualified.

Instead of using vague language about the experience or skills candidates need in job postings, be more precise about expected qualifications. When organisations ask for specific levels of experience and skills, more women that meet those requirements are likely to apply.

Women hold fewer leadership positions

The article, titled “Whether to Apply,” opens with a question that a BBC interviewer posed to Donna Strickland, a Canadian Nobel laureate in physics, in 2018: “Why are you not a full professor—given your eminence?”

The question was met with a period of silence before Strickland answered simply: “I never applied.”

That’s just one example of a high-achieving woman choosing not to put herself forward for a high-level position. Coffman’s latest research follows previous studies she has conducted that show women lack confidence in their ability to contribute and perform in stereotypically male fields and that employers often favour men for jobs in those fields.

These forces likely contribute to the significant gender leadership gap. In fact, a 2023 LinkedIn study of workers in 163 countries shows that women account for about 42 percent of the workforce, yet the share of women in senior leadership positions is 32 percent—and at the C-suite level, female representation drops to 25 percent on average.

Vaguer job qualifications push women away

To determine how men and women respond to job ads, Coffman and her colleagues ran a first experiment on freelance job platform UpWork, where job-seekers complete extensive profiles outlining their education, credentials, scores on skills tests, and work history. The team acted as potential employers and sent similarly skilled UpWork users ads for short-term positions that put an emphasis on managerial or analytical acumen. The ads called for expertise in these stereotypically male domains that struggle with female underrepresentation and lack of advancement, Coffman explains.

The ad language was fairly generic:

“We are looking for candidates with [management expertise/experience in analytical thinking], as demonstrated through education, past work experience, and test scores. Successful applicants will also have strong writing and communication skills.”

The researchers offered an “intermediate” position, as well as an “expert” track that was considered more challenging but also came with more pay. Candidates had to choose which position to apply for, if any.

When the ad contained this vague guidance, qualified female workers were less likely to apply for the advanced opportunity than qualified male workers. In fact, just 6 percent of qualified women applied for the expert job, compared with 22 percent of qualified men.

However, 29 percent of women from the applicant pool responded when the team provided clear guidance on the required qualifications in its ad, instructing people with an exact threshold of analytical or management UpWork test scores to apply to the advanced position.

“Reducing ambiguity around expectations can help people recognise that they are qualified,” Coffman says. “This likely draws in people who would otherwise fail to recognise they are above the bar.”

Clarifying job candidate expectations attracts female applicants

Next, the research team recruited new participants on the research platform Prolific to participate in a follow-up experiment, again probing their willingness to apply for an “advanced opportunity.”

Participants first completed a test in science, math, and mechanical comprehension, which was drawn from the Armed Service Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) exam. Prolific users also completed a brief sociodemographic survey and built a resume that included their test score, basic education information, and details of their work quality and history on the Prolific platform.

Similar to the UpWork experiment, some participants received only generic information about parameters for the expert job, while others received more specific details, including the desired test score.

The controlled setting allowed the team to ask several follow-up questions, analysing participants’ beliefs about how qualified they were; how high they considered the bar for the expert job; and how objective, specific, and clear the required qualifications were in the job ad.

Echoing the results of the first study, when the advanced job opportunity included only vague information about its requirements, only 42 percent of qualified women applied, compared with 56 percent of qualified men. But when researchers gave more specific guidance about desired test scores, up to 62 percent of women from the pool applied. In this study, the more specific guidance also increased the likelihood that qualified men applied.

How to broaden your applicant pool

What should a hiring manager intent on fielding more female candidates for high-level positions do? Coffman offers some advice:

1. Steer clear of vague qualifications.

Companies may want to avoid using fuzzy, subjective catchphrases to attract seasoned employees, such as “several years in the industry” or “demonstrated excellence in the field,” the researchers say.

“Our studies suggest that reducing ambiguity around required qualifications may help to draw more talented female candidates into an applicant pool,” Coffman says. “It could be a low-cost way for employers to grow the set of qualified, female applicants.”

2. State the amount of experience and the skills candidates should possess.

“While it may not always be possible to remove all ambiguity about required qualifications, try to be specific when you can,” Coffman says.

“Could you provide a specific number of years of experience? Or, give examples of what demonstrated excellence might look like. [Job ads] that are concrete, objective, and clear all work in the direction of reducing ambiguity.”

3. Actively recruit qualified female candidates, rather than wait for people to apply.

Managers shouldn’t take for granted that “the best people will rise to the surface, raise their hands, and say, ‘Yeah, I’m great,’” Coffman says.

“It’s important to realise that we can’t just rely on people to put themselves forward and assert themselves. Stereotypes and bias may contribute to women being less likely to recognise their expertise and qualifications, particularly in domains that have been dominated by men historically.”

For that reason, recruiters should consider being more proactive and widening the pool of candidates they consider, rather than sitting back and waiting for people to volunteer themselves.

In ongoing work, Coffman continues to unpack the factors that lead to the under-representation of women in male-typed fields. She is currently studying how candidates seek out and process feedback about their skills and how employers’ choices about what types of information to use in hiring decisions perpetuate existing gender gaps.

“How can we increase the number of talented women in the pipeline for these top positions?” Coffman asks. “And, once they are there, how do we make sure employers give them a fair shot? Solving one of these challenges without addressing the other is unlikely to lead to sustainable progress.”

This article was written by Kara Baskin and originally published by the Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.

Related Posts