This is a guest post by Mehran Nejati, Senior Lecturer in Management and Azadeh Shafaei, Lecturer in Management at Edith Cowan University.

We spend, on average, about 90,000 hours at work.

Given this, most of us want work that’s more than just a source of income. We want work that’s satisfying, significant, valuable. Work, in other words, that is meaningful.

What makes any particular job meaningful is, of course, subjective. In the mid-1970s, though, economist Greg Oldham and psychologist J. Richard Hackman identified five common factors:

- More skill variety,

- Task identity (doing a job from beginning to end with a visible outcome),

- Task significance (making a difference to someone or something),

- Autonomy, and

- Feedback all help make a job more meaningful.

But there are also organisational characteristics that “lift all boats”, contributing to everyone’s sense of meaningful work. In our research, we have investigated the role of three key factors – environmental consciousness, social responsibility and inclusive leadership.

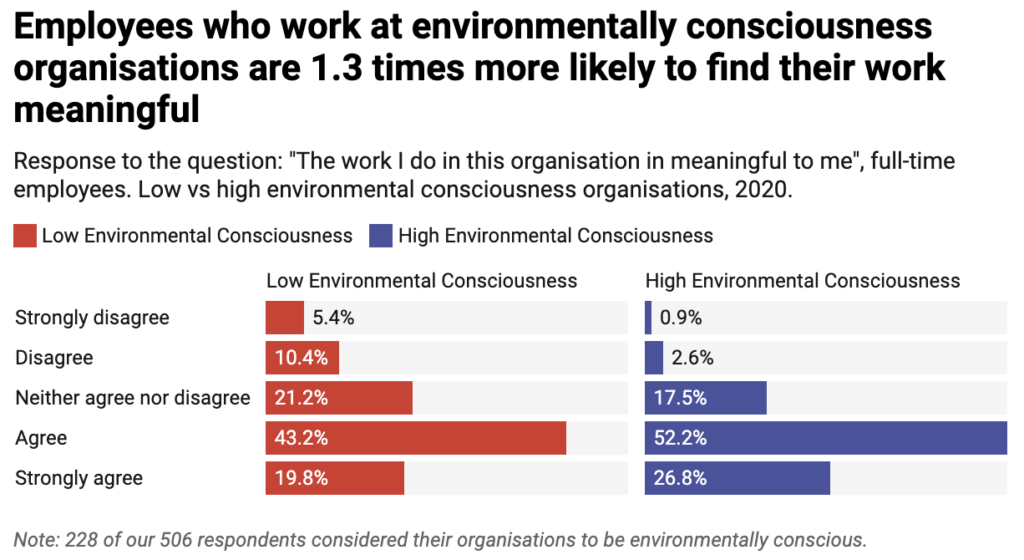

We found employees who rated their employer as environmentally conscious were 25% more likely to consider their work meaningful than those who didn’t.

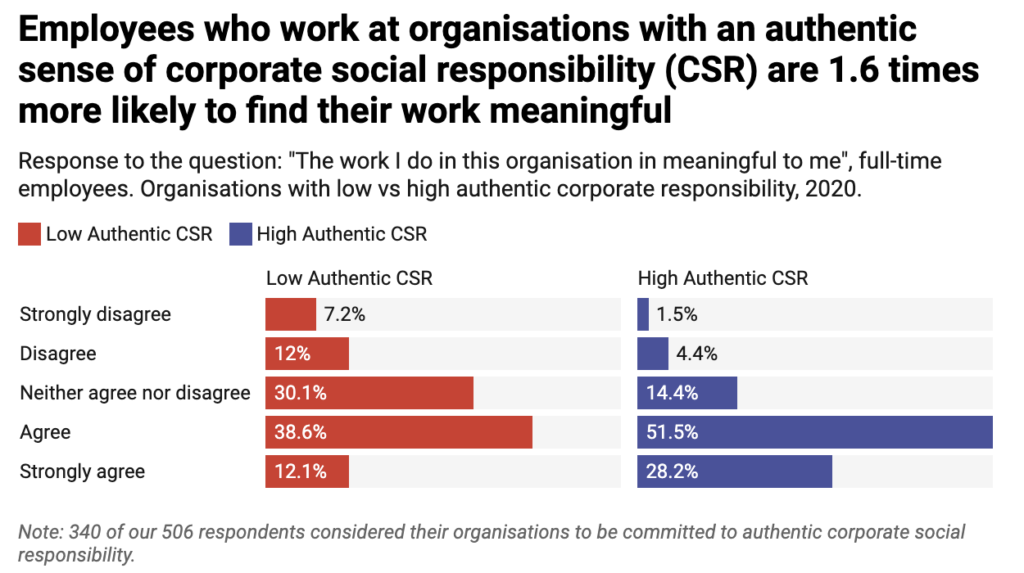

Those who believed their organisation was committed to corporate social responsibility were 59% more likely to think their work was meaningful.

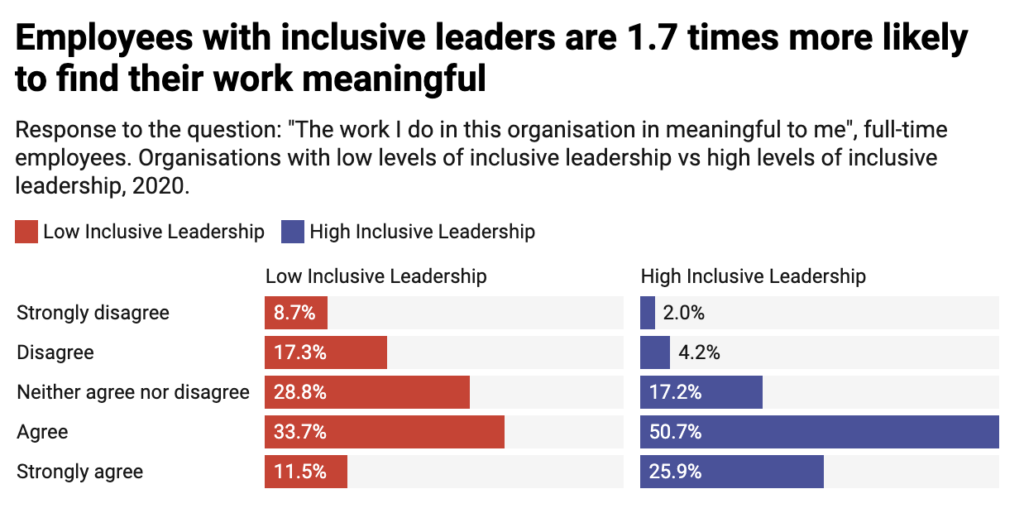

And those who considered their supervisors to be inclusive leaders were 70% more likely to find their work meaningful.

Why meaningful work matters

Meaningful work outranks compensation, perks and other factors in career importance across all age groups, according to a 2019 survey of more than 3,500 workers in the United States, Canada, Ireland and Britain.

That survey, commissioned by software company Workhuman, found meaningful work becomes more important to us as we age. Those with sense of meaning and purpose were about four times more likely to love their jobs.

Our research involved surveying 506 Australians working full-time across a broad range of occupations and position levels in service and manufacturing organisations.

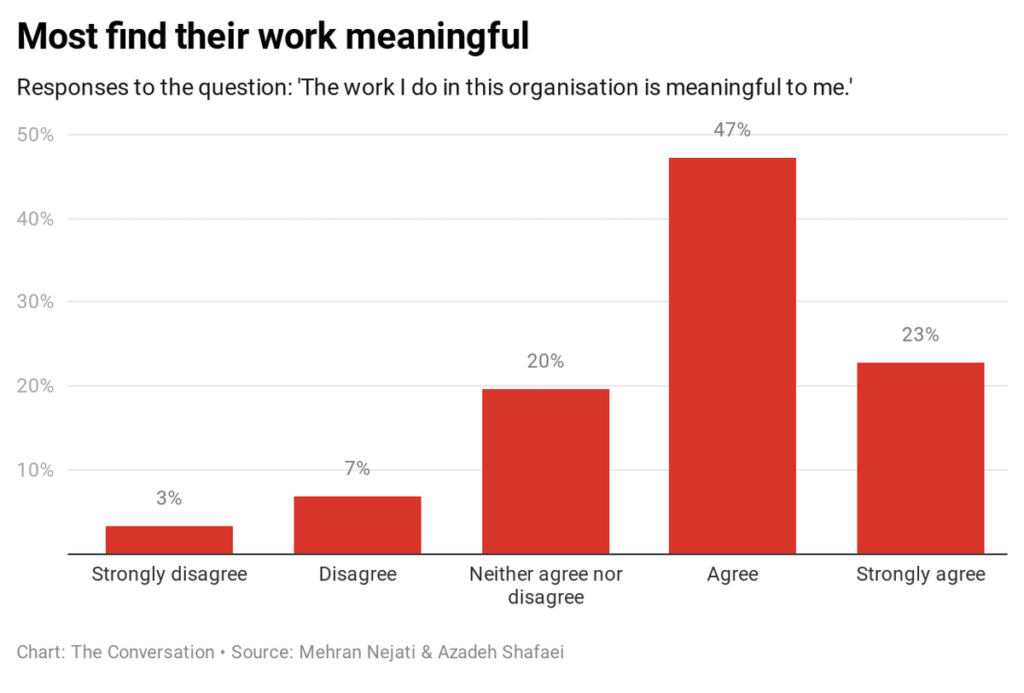

About 70% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed their work was meaningful to them. About 20% were neutral. Slightly more than 10% disagreed.

To assess the contribution of organisational-level commitments to meaningful work, we asked our respondents to rate their workplaces’ level of environmental consciousness, social responsibility and inclusive leadership. We then examined how each employee rated the meaningfulness of their own job.

1) Environmental consciousness

Respondents rated their organisations based on criteria we gave them. To assess environmental consciousness, for example, we asked employees to consider three elements of “green human resource management” as evidence of that environmental commitment:

- providing training and information that enabled employees to understand the environmental impact of their activities and decisions. This would include educating employees on how to reduce waste, water use and carbon emissions

- including environmental impact of actions and decisions in employees’ performance assessment, with real opportunities for staff to contribute

- recognising and rewarding employees for their contribution to environmental goals. This might be done, for example, through awards.

Among those who rated their organisations highly on environmental consciousness, 79% said they found their work meaningful. This compared with 63% of those who considered their workplace to have low environmental consciousness.

2) Corporate social responsibility

We defined authentic corporate social responsibility for our respondents as not just policies but actions demonstrating a genuine interest in the welfare of all stakeholders affected by the organisation’s practices.

In contrast, symbolic corporate social responsibility would be done mainly as a marketing exercise.

Among those who rated their organisations’s commitment to corporate social responsibility highly, 79.7% said they found their work meaningful. This compared with just 50% of respondents who thought of their employer as not having genuine interest in social responsibility.

Those who felt their organisations were authentic about corporate social responsibility were 67% more likely to say they loved their job and more than twice (or 230%) as likely to say they felt proud to work for their employer.

Inclusive leadership

We defined inclusive leadership for respondents as a management style showing openness, accessibility and availability to others. Inclusive leaders value employees for their unique contributions and make them feel a sense of belonging to the organisation and team.

We asked employees to rate their direct supervisors or leaders using several criteria as evidence of an inclusive style, including:

- did they listen to employees’ requests?

- were they available for consultation on problems?

- were they open to hearing new ideas?

- were they open to discuss the desired goals and new ways to achieve them?

- did they encourage employees to access them on emerging issues?

Among those who rated their leaders as being inclusive, 76.6% found their job to be meaningful. For those with non-inclusive leaders, just 45.2% found their work meaningful.

Inclusive leadership was also associated with more innovative behaviour. Those working for inclusive bosses were 5.4 times more likely to say they generated original solutions to problems than those with non-inclusive bosses.

Work can be exciting and meaningful, and not experienced as mere work. By showing authentic commitment to social and environmental responsibilities and having inclusive leaders, organisations can create a more meaningful work for employees, enabling them to thrive.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Posts